One of our favorite aspects about this whole project is that it’s a family endeavor: not only are you all cousins, but you also created 4th WORLD PRESS, an independent family-owned publisher. Can you tell us a little bit about the inspiration behind the book, as well as the decision to self-publish?

Andy: I had been floating around the idea of writing this story for about four years prior to us publishing the book, but while it was always on my mind, no one took it seriously, not even myself, took it seriously. Then around the time I was finishing graduate school, my paternal grandfather passed away so I was reflecting a lot on the roots of our culture and started doing more personal research on Vietnam -- its history, the art, culture, and of course, the Vietnam War. But I noticed that our narratives centered around the war, which is a very important part of our history and should never be forgotten, but that was over forty years ago. Since then, we have become so much more as a community, especially those who are now “Viet Kieu,” or Vietnamese people living outside of Vietnam. I kept asking myself, “How do we as a culture and collective of Vietnamese and immigrant Americans evolve our narratives, yet continue to carry the cultures that made us who we are?” I know that I am a product of the war, but I don’t feel the gravity and connection to the war that my parents do, and so I was searching for a story that I fully identified with.

Fast forward two years, I thought it'd be amazing to team up with family for this personal creative endeavor and so I first sought out Phuong Nam, who had been a piano instructor in her past life, to see if she was interested in making music for a potential audiobook. She agreed, and so then I reached out to Thi, who thankfully was more than excited to jump on board as our illustrator. At the time, Thi was creating more and more paintings, working on professional creative projects for art shows and even for the mayor of her town. I admit, at first I was nervous working with family because although we are cousins, Thi and Phuong Nam are sisters, and so it was a risk because this project could either bring us closer together or damage our relationships. But I thought it would be so dope for us to combine our powers together as a family and take a traditional children’s book and add additional dimensions, like audio narrative and digital book formats, to make it really unique.

After everyone was on board, I proceeded to write the story based on our individual and shared experiences. As I was writing, it felt like I had been writing this story my whole life. Before figuring out the prose, I talked to many people about their Asian American experiences and so the writing process was actually much faster and came more naturally than I had anticipated because of this research. After sending what I had to my cousins, they added their own perspectives and ideas too so this story really does have elements from each of us. We shared the initial drafts with a small number of friends to gain perspective and to see how it resonated with everyone, and then when we were near the final draft of the story, Thi went to work on the illustrations. As the second illustrative draft was maturing, we started brainstorming the sound palette for Phuong Nam to begin work on the piano piece.

We decided early on to self-publish because even though it may be a grander ladder to climb, we wanted to be able to control our story, our vision, and our direction, so that it would be authentic to our intentions and values. We wanted to sell directly to our readers, cut out the middlemen, and invest more money into the quality of the book, instead. At first, we thought that the book would be meaningful just for our family, but as we got deeper into the project, we realized how powerful this book could be. Our hope is that this book goes global and we can translate it and modify it for different markets. All of this got us thinking about potentially starting a publishing company, and that’s how 4th WORLD PRESS came about. The name 4th WORLD PRESS comes from a number of things. The color green holds a great deal of significance for us, and one of my friends told me green is related to the 4th chakra, the heart, which embodies love and compassion -- two themes that are a huge part of our message. 4th World also refers to the classification of hunters and gatherers and themes of self-sufficiency and independence, which resonated with us because we wanted to self-publish so that no one else could curate our story or dictate our timeline. This whole entire process of writing, illustrating, composing, and publishing this book has brought us all closer together and able to better understand one another, and I couldn’t imagine doing this project with anyone else.

Thi: I was also nervous about working together with my sister and my cousin, but I think that there are two important things that helped. First, a vital component of growth and improvement for anyone is feedback. But as an artist, feedback is often hard to hear because you're putting yourself out there when you create, which can lead you to feel very vulnerable. But with Andy and Phuong Nam, they expressed their feedback in such an honest and kind way. Secondly, I think that we also all have strengths and weaknesses that are really complementary to each other. For example, Phuong Nam is very patient whereas I’m very type A, and with Andy right in the middle, we help balance each other out.

Pictured above: Andy, Thi, and Phuong Nam.

Your children’s book (which is great for adults too!) centers the Vietnamese-American experience, a fact that resonates so deeply with many of us because we didn’t have books that reflected faces and stories like ours. While you do provide a Glossary at the end of the book, you intentionally did not translate most of the Vietnamese phrases in the actual story, creating a way for folks who speak Vietnamese to connect to the story on a different level. What went behind the decision to make this book not just by Vietnamese-Americans, but also for Vietnamese-Americans?

Andy: When we sought out to write this book, we wanted to create as authentic of a story as possible, and with all three of us being Vietnamese-Americans, it made sense for the characters to be as well, naturally. With that being said, we also felt that although the story is unique in certain parts, with Vietnamese-American characters, culture, and themes, it could resonate with other Southeast Asian Americans and immigrant Americans.

Phuong Nam: I feel that this story will relate to anyone who struggled with identity issues growing up.

Thi: I agree. One of the most surprising things (and one of my favorite things) about this whole process has been people’s reactions to the book. A person who bought the book, who is not Vietnamese-American but does identify as LGBTQ+, really identified with the themes of being different and learning how to embrace your differences. It was nice to hear this feedback because we were able to see how our book can resonate with people outside the Vietnamese-American community as well.

A familiar refrain for many refugee and immigrant families is the experience of having to straddle two different worlds, constantly negotiating the lines of where one identity begins and the other ends. This book does such a great job of illustrating what it means to be Vietnamese-American and seeing this complicated in-between and reminding us that home is not necessarily a physical place. What is a memory you have of feeling Othered, or conversely, of learning to embrace the hybridity?

Andy: A lot of this book draws from my own experiences of growing up in a time before Portland was Portlandia; there weren’t a lot of people of color, and the majority was white, small town folks, and racism wasn’t unusual. I got made fun of and beat up for my chinky eyes and for wearing a Buddhist necklace. I remember this one time on the playground when a kid stopped me in the playground and asked, “What are you?”, which led to more kids following suit and repeating the question, “What are you? What are you? What are you?” I looked around, also questioning what I was. I knew that I wasn’t a White person or a Black person, and so I just said I was both. That was my first memory of being alienated and feeling like I didn’t belong in this society. My parents are Vietnamese but they never explained what being Asian American or Vietnamese-American means, and even at home, I’m more Americanized than my parents and sister, so that can feel strange sometimes too.

The borders in Vietnam reopened in the early 90s and I was able to visit Vietnam in 1993. I was in grade school and remember thinking, “I’m going home to Vietnam!” but when I got there, I realized that I was an American with skin light as hell compared to everyone else. I was sitting with my grandpa on the sidewalk and suddenly these Vietnamese kids came up and started throwing rocks at me. My grandpa got up and chased them away, but it didn’t dawn on me until later that those kids didn’t like me because I was American. I realized how I didn’t belong in America and I didn’t belong in Vietnam. Going home that day, I thought about it more and in my sadness I rationalized how it must mean that I’m a child of the world -- that I’m of both places and cultures. Growing up in the Buddhist temples also helped shape my thinking because of teachings like how we all are one, that we must treat every living being as equal, that we’re all part of the universe -- these lessons taught me how to be resilient in the face of alienation. And so when I was writing this book, I drew from this and my other childhood experiences of being between worlds and navigating those spaces.

Thi: The three of us grew up with very different experiences when it came to navigating feeling different from others: Andy was cruelly bullied for his slanted eyes, Phuong Nam had to endure butchering of her name and her own mishaps with the English language (e.g. yo-yo is a plastic toy, not a potato wedge), and I was constantly judged on my appearance using a Western ruler to measure beauty (fair skin, narrow nose, double eyelids). We journeyed on our own paths to reconcile and embrace what makes us unique. But like many of us, it’s a similar story of learning self-acceptance, just painted in different colors.

Phuong Nam: Growing up with what I consider a more challenging name for English speakers has really helped mold my identity. I was taught to love my culture and in doing so I love my name because it’s unique and I wouldn’t ever want to change it. I’ve learned to adapt my name to sound more Americanized to make it easier and to be more understanding that tonal sounds are hard for those who didn’t grow up learning more than one language. In the story, Quyền is a very strong female character and her name really represents her identity, which I think many can relate to in regards to having a beautiful name that isn’t English.

The illustrations in this book are just so beautiful, and reading Thi’s blog post on some of the hidden Easter eggs made us fall even more in love with the artistry, the intention, and the symbolism that imbues each page of this book. Thi, can you walk us through the process from conception to final design?

Thi: This is the first book that I have ever illustrated so this was a learning experience, and also why it took so long! First, after we finalized the prose, I had to draft a storyboard to conceptualize composition and imagery. Afterwards, I designed the characters. There were hard lessons along the way, like in the first draft where I used whatever color I could reach for, but after some reflection, I realized it was more important to limit the colors to a specific color palette so everything could tie together more cohesively. It was important that the colors were chosen with care and intention. For example, colors were used to convey emotions or a mood, and others were chosen as a nod to the Vietnamese culture, like the color jade alluding to the precious jade stones often adorning Vietnamese jewelry.

Andy: What I love about the illustrations is that we tried to infuse as much art from Vietnamese culture and history as possible. When I was researching, I noticed that there were a few big, distinct waves of Vietnamese art, including food, music, pottery, and poetry. So a huge reason why our book is written in poetic form is because it’s an ode to Vietnamese prose and poetry. For the illustrations, Thi used watercolor, which is a popular Vietnamese art form, and she did a great job of modernizing the style. Vietnamese pottery, known then as Annam ware, was really popular during the 14th century when Chinese would manufacture the pottery in Vietnam and then sell them to other countries like Japan -- Thi brilliantly incorporated elements of the pottery into the book’s illustrations, including the iconic cobalt blue color.

Thi: Originally, I had planned on creating only two drafts after the storyboard, but I was not completely happy after that second draft, not only because of my perfectionist issues, but also the desire to offer something that I would be proud of, one hundred percent. But creating one more draft would require possibly another half a year because of my full-time job and only being able to work on the project before and after work. I approached Andy and Phuong Nam with this dilemma and they were completely supportive of my recommendation to create one more draft that could offer even better artwork. That's a value we share: creating something of quality and not compromising.

Photo by Greg Abraham.

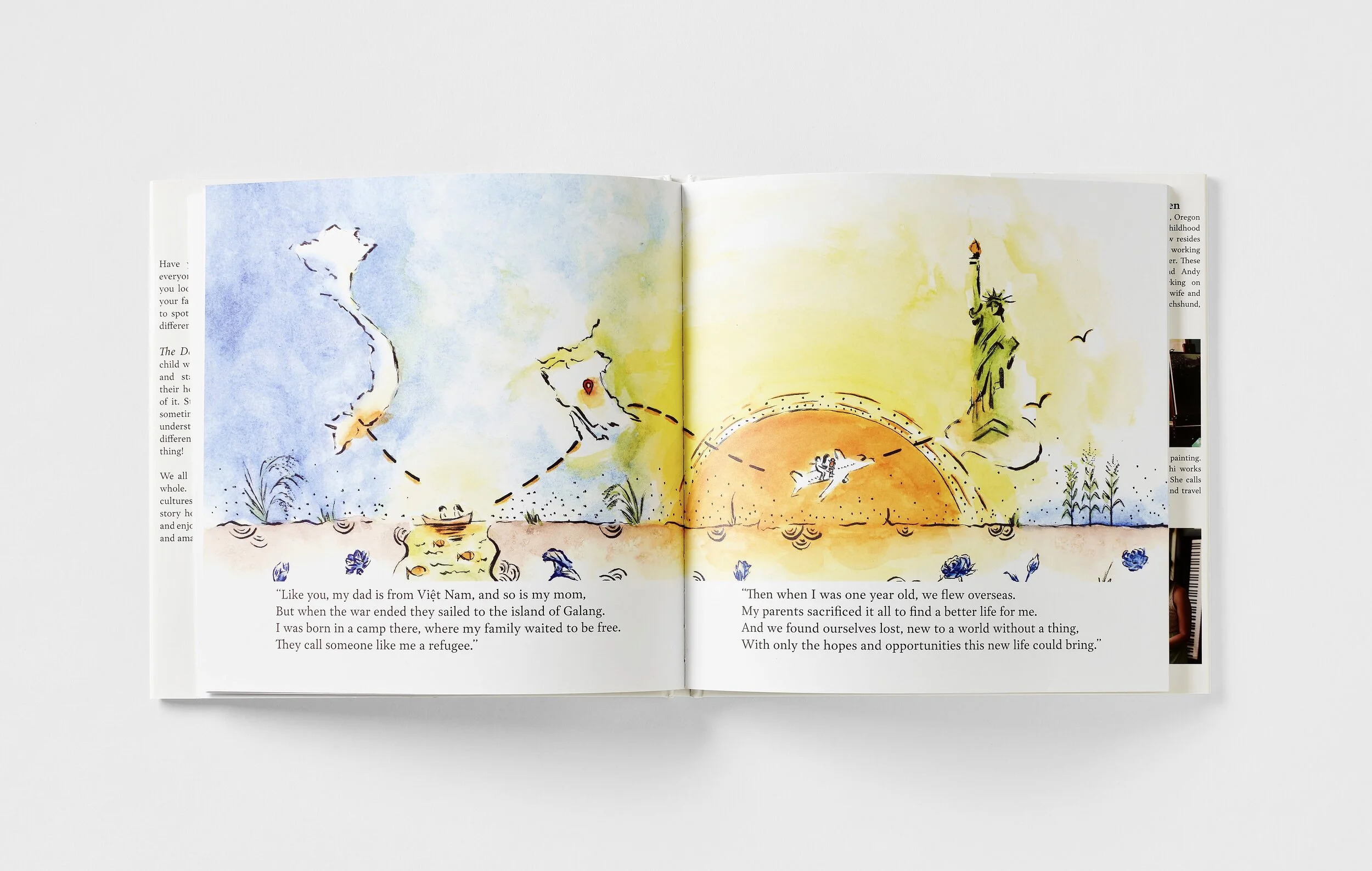

I actually thought the 2-page spread where it shows the journey from Vietnam to the refugee camp to America would be the hardest to illustrate, but it was actually the food page that I had to redo several times, and the more I messed up, the more nervous I was. It’s a mindset thing: it was hard because I came into it with a fear of failing from my previous attempts I had not been happy with. I also wanted to find ways to balance out the heavier themes in the story with some lightness through the illustrations, like with the dogs that you see throughout the book. The dogs bring levity, help with foreshadowing, and help elaborate the mood of the book scenes. I also wanted to be sensitive in my use of color. Like in the scene where Anh gets bullied, while I wanted to use color to convey a specific mood of the scene, I didn’t want to reach for the color black for the bullies; we didn’t want to play up stereotypes or offend anyone.

Photo by Greg Abraham.

Andy: We also wanted to be authentic to our own experiences too: when I was growing up in the 90s, it wasn’t the Black or Latino kids who bullied me, but the white kids. And when working on this book, the goal wasn’t to continue the cycle of hate, but rather, to channel that negative energy into a product of positivity. We were intentional about not wanting to alienate anyone because we know that everyone can resonate with being bullied. So we used Thi’s illustrations to create a specific mood that could speak for itself. Bullying, othering, being made to feel different -- these can come in many different forms. For example, in school no one could ever say Phuong Nam’s name right, which made her stand out in ways that made it difficult for her; they didn’t recognize there is a deep meaning and identity tied to her name.

You are currently working on the audiobook soundtrack, the third dimension of this project. Phuong Nam, can you tell us what it has been like for you working on both the theme song and the audio narrative?

Phuong Nam: I started playing piano when I was younger because one of my friends played piano. My parents also thought it was a good idea because I couldn’t sit still at that age and they thought piano would help by teaching me patience, and I guess it worked because I took piano lessons for about ten years.

It was a big challenge for me to work on the theme song/audio narrative as it had been many years since I’ve sat in front of a piano again. Composing is way harder than following a book of notes already laid out for you. I had to refer back to basic theory in books and video tutorials to refamiliarize myself with different chord progressions and how to create sad and happy melodies. Mainly, I did not want to disappoint my cousin and sister if it wasn’t a good piece. They were very encouraging and always supported me during the process. I worked on creating sounds that reflected the emotions of the characters and I wanted it to have a slight Asian melody to the piece as a nod to our roots. It helped a lot to listen to Andy’s prior recordings of the book readings in order for me to pull the moods and emotions from words into musical notes.

Andy: One of the deep honors of these kinds of collaborative projects and especially if you’re lucky enough to be able to work well with the people you love--the growth experienced within each part and each person means that much more. We are definitely proud of Phuong Nam and how far she developed as an artist. After she finished her piece, we then took Phuong Nam’s original piano composition recordings and jumped into the studio with my good friend, Gyrefunk, an amazing multi-talented artist from the music group, TRKRNR, who helped produce, engineer, and arrange the scored piece to make our ideas come alive.

While the story follows a little boy named Anh, there is also a character named Quyền, a little Vietnamese-American girl who helps guide Anh through his journey of self-acceptance. This character plays such an important role in the story, serving as a catalyst for conversations about the refugee and immigrant experience, double-standards, colorism, and so much more. What were some of the ways you hoped to use these two characters to challenge or expand what it means to be Vietnamese-American?

Andy: The Vietnamese-American community and experience is not a monolith. Anh was born here; Quyền immigrated to the United States. Anh is lighter skinned; Quyền is darker skinned. I had always envisioned that there would be two characters, one male and one female, and I didn’t want one voice or storyline to dominate the other. For the male character, Anh, I chose not to introduce his name in the story because to me, he represents the part of us who start off life not really sure of our identity. To me, it made sense that Quyền was going to be the guide figure because of her backstory and the maturity that comes with it. In my family, the women are the leads, heads of households, the steady hand, the role models, and I wanted that to come through in the book.

Thi: There are definitely nods to feminist themes throughout the story, and even in the illustrations. Thinking about the challenges Vietnamese-American women face in terms of aspects like beauty and gender roles, I remember how my mom would tell me that I should embrace the good of both cultures, but at the same time she would also always ask me why I’m trying to get tan and that I should keep my skin fair. I grew up hearing a lot of judgment on my and other girls’ appearances using a Eurocentric ruler: double-eyelids; long, thick eyelashes; straight, narrow nose; fair skin. So in one illustration, I drew Quyền split in half to show the contrast between what society tells her she should look like (in a dress, lighter skin, and long, flowing hair) versus who she really is. There was another scene I illustrated that incorporated expected gender roles, something that is imposed in many cultures, where Quyền was shown cooking and cleaning, and hiding herself. These were painted in mostly monochromatic colors as a metaphor for the lack of different aspects of who we are and can become when we are confined to just one mold. One story that happened to me that I really just chuckle at now is when I got engaged, my family was having dinner with my now mother and father-in-law and at one point, my dad stood up, unsolicited, and apologized to my in-laws because I don’t cook.

Your book is coming out at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has unfortunately led to huge spikes of anti-Asian sentiment and violence across the nation. Of course this is only one of many examples where the racist ideology of “Yellow Peril” has punctuated the Asian and Asian American experience. And reading The Day I Woke Up Different against this backdrop made us emotional because your book serves as such a clear reminder of how much love, pride, and resilience our communities embody. What is the impact you hope your book leaves?

Andy: Growing up I experienced both indirect and direct racism: I got spit on, I was involved in fights, I experienced alienation and microaggressions. The only way I was able to overcome that was to have unwavering self-belief, grit, and self-love. I learned from the Black community through hip-hop and house dance culture, watching how the artists were so unapologetic for being themselves. I learned it was okay to appreciate yourself. So the more I practiced that, the more I started to appreciate all the pieces I have as well as didn’t have. And I realized you can hate all you want, and while hate and fear has its limits, love is limitless -- you can never put a cap on it. The more people hated on me, the more I would revel in my success and love. So this book’s ending is actually about the start of that journey, of unwavering self-acceptance. I hope readers of this book, both now and in future generations, become inspired to start their own journey or if they are already on that path, to remind them to reflect back and be proud of how far they’ve come.

Thi: Our mission was never to sell a certain number of books or make a certain revenue. It is a passion project and even if we don’t make any money off of it, it’s still worthwhile to us because we get the opportunity to express what we’ve been thirsting to express from our hearts. I hope that this book guides children and adults to not feel ashamed of who they are and have the courage to discover all the beautiful aspects of what makes them unique and special. We are a potpourri of different things and that’s not only okay, but something we should embrace.

Phuong Nam: I hope that this book either gives hope and strength to those who have struggled with self-discovery, hate, negativity, or bullying. And it gives perspective and a voice to those who need it.

4th WORLD PRESS is an independent family-owned publisher. Through the magic of literature, visual illustrations, and audio content, we tell stories of the unheard voices and distribute those messages to our communities.

Website: https://4thworldpress.com

Instagram: @4thworldpress

Facebook: @4thWorldPress

Twitter: @4thWorldPress