Can you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

I’m a second generation Vietnamese American storyteller from Orange County, CA. I currently introduce myself as an actor/singer but I definitely hope I’ll get to say director/producer within the next five years. I was classically trained for the stage, but I moved to LA four years ago to pursue Film and TV.

When and how did your family arrive in the United States?

Both my parents were boat people. My father arrived in 1975, my mother in 1982. My father’s story is kind of crazy. Two of my uncles and one of my aunts had paid for spots on an escape boat; they were the only ones initially trying to escape before the Fall of Saigon. My father went to visit wherever they were staying near the ocean as they waited to be told when to make their attempt at escape. The last night, however, some other person backed out, and my father talked his way into joining his brothers and sister in law. Because the Americans had not officially pulled out of Vietnam yet, American and British ships were patrolling the ocean surrounding Vietnam and their boat was spotted by Americans within a day or so. They were taken to Guam for a couple months before finally being placed for resettlement at Camp Pendleton in California. An amazing American family fortunately sponsored them — they actually still consider us extended family. With their initial support, the four really found a way to flourish as resettled refugees. Family reunification laws allowed them to eventually sponsor and bring over my mother and the rest of my family — more than half fled as refugees and the rest (i.e. my grandparents) emigrated in the 90s. I’m pretty fortunate. I grew up knowing both sets of my grandparents and all my immediate aunt and uncles.

What was it like for you growing up as a Vietnamese American? Was there ever a moment when you felt extremely ashamed or extremely proud to be Vietnamese?

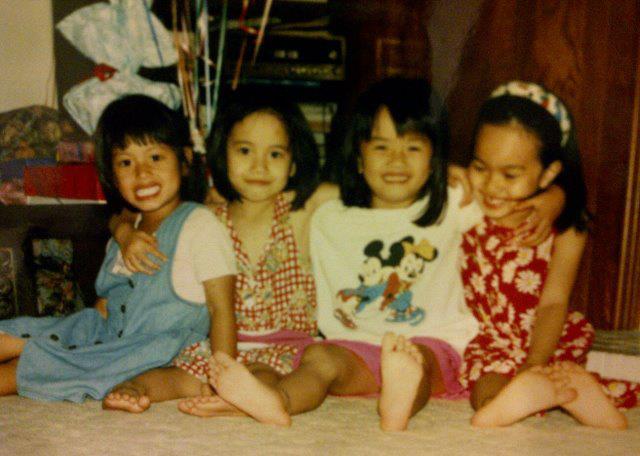

Growing up Vietnamese in Orange County is both a blessing and a crutch. You can really thrive in that oasis — there are close to 200,000 Vietnamese Americans that reside in the county. There were pages and pages of Nguyen’s and Le’s and Tran’s in my high school yearbooks. I specifically was raised in Fountain Valley. It’s still part of the Vietnamese community but on the outskirts of Little Saigon, which tends to be a bit more working class at its center. I had a privileged white collar upbringing in FV as both my parents were engineers. I’ll admit my childhood does often echo the “Model Minority” narrative society associates with upper class East Asian Americans. Leaving the bubble can very difficult however when you don’t realize just how sheltered you are from the reality that you and your people are indeed a minority in the States.

I was mainly aware of being a minority due to the lack of media representation. I remember battling feelings of shame as a kid over my “Asianness.” I definitely had those thoughts too of, “If I can’t be the ideal of White, blonde haired and blue eyed why couldn’t I at least be one of those ‘good Asians’ and Japanese or something.” There was an unspoken belief that East Asian cultures were more sophisticated and refined. I even hated the way Vietnamese sounded compared to Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean. There was also the added layer of being tan/darker skinned within the Vietnamese community with its beauty ideals that prefer milky white pale skin. I consider myself light skinned in the general spectrum of things but I am dark enough to have faced colorism. It wasn’t unusual to hear Vietnamese folks muse on how “đen” (dark) I was in the summertime. All these things played a part in the levels of shame I felt as a kid for not just being Asian but a borderline “brown” SEA. The older I get though, as I keep learning more about myself and my people, I’ve become extremely proud of being Viet/SEA and wouldn’t identify as anything else ethnically and culturally.

Did you always know that you wanted to become an actor? What key moments or experiences in your acting journey have helped shape how you see the world?

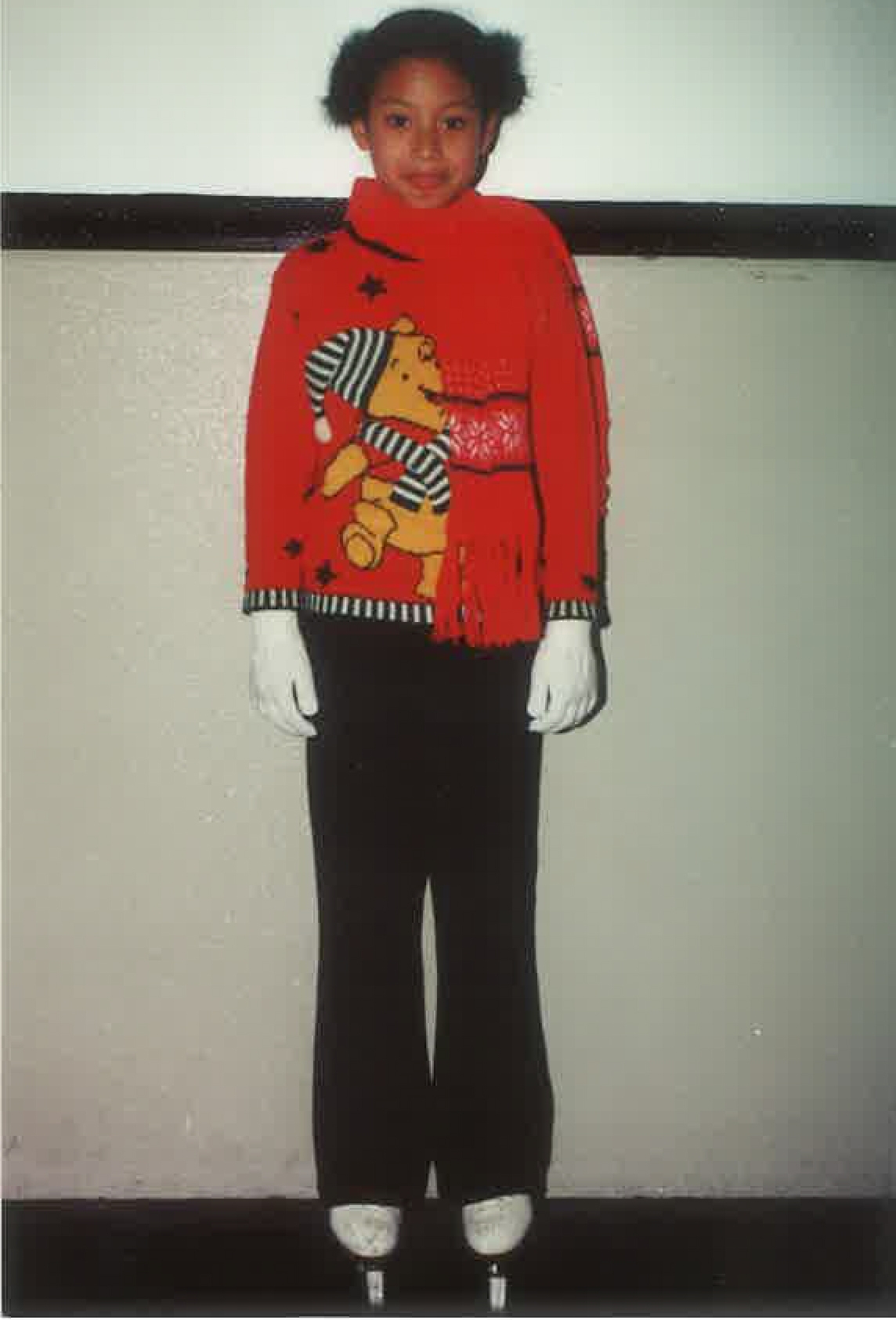

I didn’t always know I wanted to act, but I grew up very artistically minded — I played piano, danced, painted, and figure skated. I’ve been performing in some form since I was 4 years old. I also was an only child with an overprotective mother, so much of my childhood was spent playing at home alone. The only time I got to be social was during extracurriculars. By the time I was 7 or 8, I had fallen in love with the adventures and stories you could experience from the world of books. I like to joke that my parents unwittingly raised me to be a performer and storyteller.

Even though my parents exposed me to a lot of art, I didn’t know theater was really a thing until I got to high school. My sophomore English teacher gave us extra credit for seeing and writing reviews of plays at South Coast Repertory, a local Tony-winning regional theatre. That same year, I went to NYC for the first time for a family vacation. At the recommendation of a stranger in the line at the TKTS booth, we got discounted tickets to Spring Awakening. The crazy energy of those young performers totally blew my mind as a 15 year old. I decided then that I wouldn’t rest until I found a way to get on a theater stage.

BTS of my high school production of Sweeney Todd when I played the "Beggar Woman"

My first show funnily was Miss Saigon a few months later. A local high school did a production of it that was open to all students in the district. No I didn’t play Kim, the lead, but I became addicted to theater instantly. I’m now a huge critic of the problematic tropes Miss Saigon perpetuates, but I do credit it for bringing me closer to my heritage. Doing research for the musical was the first time I took an active role in learning about my people’s history and culture.

It wasn’t long after that first show that I made the brash decision to pursue this “acting thing.” I wound up studying “straight acting” (the non-musical kind) at the University of Minnesota’s conservatory program affiliated with the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. I thought I’d finish school and do regional Shakespeare my whole life — TV and film didn’t seem a place for someone who looked like me. In theater, the suspension of disbelief allowed for unexplained “color inclusive” casting. The culture shock, though, of being somewhere that felt far less diverse than SoCal really affected me. I got so tired of feeling like a token Asian and started confronting what it meant to be an Asian American artist.

My drama school cohort

The Hidden People: Part 1 by Joe Waechter at the Guthrie Theater

I noticed the theater goers in Minneapolis reflected a specific, privileged demographic — a very upper class and White one that I became less invested in over time as a storyteller. It didn’t matter if it was a production at the Guthrie, Penumbra Theatre (the Black theater company), Mu (the Asian Am theater company), or some other theater outside of the city or state. This understanding about audiences reinforced my belief that art, especially “highbrow” art, often feels like an inaccessible privilege. Because of this, I found this desire to create content that sits somewhere between commercial mass entertainment and nuanced art. I don’t want to keep upholding these pretentious economic and social barriers of entry.

At the Shakespeare's Globe in London

The dynamic between myself and my “company”/graduating class at drama school really played a huge part in the way I viewed my identity and how it influences our work as artists, especially when collaborating with diverse voices. Despite being surrounded by a very white general student population of over forty thousand students, I was fortunate to spend much of my time amongst a fairly diverse set of 16 other actors that I learned and grew with for 4 years. Yes, I did feel this weight of being a token Asian from time to time, but I wasn’t completely alone. There was a Filipino girl in my class and about half of us were minorities of some sort. It was a confusing time for us all and we had many moments as a dysfunctional family, but the diverse environment of my company taught me that intersectional spaces and groups can yield amazing dialogue and art. As I spent most of my time with my company, my best friends in college happened to be Black, Jewish, and/or queer. We had a lot of amazing dialogues concerning race, culture, class and how our experiences intersected and differed. We bonded over feelings of alienation in what felt like a sea of conservative blonde hair at times. Even when butting heads, we felt this strong sense of understanding and support. Those friendships served as both a life line and a source of challenging growth during my time in Minnesota — it’s certainly been a touchstone of how I view my identity as an intersectional-minded and socially conscious artist.

Are there any plays or movies that have really inspired you as an artist?

There are two key pieces of writing that have really informed how I view the world and art. My Dramatic Lit professor in college assigned Aimé Césaire’s Une Tempete and excerpts from Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. Fanon’s theories and analysis of the “colonized intellectual” resonated so deeply with me. I’m not French Martinique, but I am a Western raised/educated Vietnamese American. Césaire’s Une Tempete is this wonderful reimagining of Shakespeare’s The Tempest from a postcolonial perspective. It made me understand how art and stories can be such an effective way to engage with political and social issues. These two works have influenced so much of how I see myself artistically and politically. They guided me while I processed my feelings of anger towards American and French culture — two things I romanticized until about 5 years ago. Towards the end of college, I began to really explore my racial and ethnic identity — not only am I Asian in America, but I also carry this legacy of my people’s oppression and colonization. I was so lucky to be highly educated, but all these big SAT words didn’t teach me how to articulate this rage that started brewing when I really began to understand our past. Seeing the term “colonized intellectual” for the first time was a watershed moment for me. I think I cried. Never had two words described both my privileges and struggles so perfectly.

I’ve actually had this idea to produce or direct a production of Une Tempete where we expand it's lens even more. The play uses the structure of Shakespeare’s Tempest to examine the dynamics between a white colonizer, a mulatto slave, and a black slave. I’d love to see Ariel played by an Asian actor instead of a light skinned, mixed race Black actor. I’m not sure if it would be appropriate to the source material, but my vision is to have Ariel represent the “Model Minority” experience. The relationships between Ariel and Caliban and Prospero would be a way then to explore the hierarchy and tension created by racial politics between multiple racial groups, rather than just a White and Black narrative. I do want to respect the play and Aimé Césaire’s original vision though. Maybe it wouldn’t exactly be Une Tempete, but an Une Tempete/The Tempest intersectional redux for Millenials and Gen Z.

You currently play Trinh Phan on the critical hit show, Queen Sugar. What does this opportunity mean to you on a professional and personal level?

Photo Credit: OWN

Oh gosh. Being on Queen Sugar has so much meaning to me, in so so many ways. I still cannot believe that my first big kid acting job is for a project that aligns so wholly with my entire soul. It’s political, intersectional, female-led. It’s this stunning love letter to Black families in the South. It paints such beautiful portraits of wonderfully complex yet deeply flawed Black men and women. I just love how human all the main characters feel on the show, something that still feels rare for characters of color. They have agency over their lives and aren’t disposable accessories for white people. I mean, I had to stop for a moment my first day on set to take in how diverse the crew was.

Photo Credit: OWN

Queen Sugar is executive produced by these two amazing queens who are the leading voices in this ongoing public conversation concerning diversity and representation in media. I’m working on an Oprah show, y’all, OPRAH. I grew up seeing her on TV and now I get to say that she’s kind of my boss — isn’t that so cool? And Ava is, hands down, one of my top 3 living heroes. It’s insane. Sometime last fall, I told myself I wanted to be a part of the “Ava Tribe,” as I dubbed it. But it was one of those bucket list items that I hoped would happen 10 or 20 years down the line. I didn’t think I’d be sitting here now, half a year later, having met her and playing a significant role on one of her “children,” as she likes to call her projects.

I still wake up and cry in sheer awe some days. I’ve had a rough roller coaster of a journey since I started acting over a decade ago, and this job has invigorated my spirit. I’ve never felt more inspired. Being surrounded by all these female directors and producers on set, many of whom were POC and/or queer was so good for me. I feel like I’m part of this family of amazing women and people of color who will be an amazing source of support and potential mentorship as I start taking the steps to produce and direct in the future. I’ve gotten to know these two amazing Viet Am actors and got to create a familial dynamic with them on screen —a dream of mine I wasn’t sure could be realized unless I self-produced.

As far as what this role has done for me professionally as an actor — it’s definitely opening doors. I still have a long way to go before I can fully thrive off acting and filmmaking, but more agencies, casting directors and filmmakers are taking an interest in me than before. Overall, Queen Sugar has had and will continue to have a positive impact on my life professionally and personally.

You portray a character from the Vietnamese American community in New Orleans, a population that not many folks know about. Had you ever been to Louisiana before this role, and what have you learned about this community since?

Photo Credit: OWN

I knew nothing about this community prior to Queen Sugar. Growing up in Orange County, I never really felt like I needed to learn about other Vietnamese communities. It took me leaving that bubble and feeling so alienated at the University of Minnesota before I felt this huge pull to know more about and connect to other people in the Vietnamese diaspora. I had this misconception that Viet Americans had achieved the American Dream — I really thought every Vietnamese community reflected that of the O.C.’s. I also didn’t know that the Vietnamese community in New Orleans is predominantly Catholic, which is different than the mostly Buddhist environment I grew up in. I learned from my father during the audition process that most of the folks in New Orleans are North Vietnamese who resettled in South Vietnam when the country was split up in 1955. The community in Orange County, on the other hand, feels predominantly South Vietnamese. The documentary “A Village Called Versailles” was a major part of my research and education about the community. I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to learn more about the Vietnamese in NoLa and their struggles post-Katrina.

Photo Credit: OWN

I had never been to Louisiana until I started working on Queen Sugar. I loved getting to know this vibrant city while I was also soaking up my first experience filming a large recurring role. Most of my trips to New Orleans had a quick turn around so I didn't explore a ton, but I had this one long trip where I was flown out for 10 days. My uncle’s good friends, who have lived there since the late 70s, took me around one day during that trip. They told me about how there were only about a couple hundred Vietnamese folks when they first came, and showed me the first Vietnamese Catholic Church in New Orleans and the neighborhoods they used to live in. I definitely feel a special connection now to New Orleans because of this role.

What are some important issues that we as a community need to talk more about?

I really want more Viets to be involved in politics here in America. Many Viets in Orange County, unfortunately, voted for Trump. The older generation is conservative, so I wasn’t surprised. But it definitely was painful to see. Being political is the backbone of what it means to be Viet. Fighting for our homeland and our people has been in our blood for at least a thousand years. To see Viets supporting a man and a party that has such disregard for the working class or anyone considered the “little guy” or “underdog” — it just boggles my mind. Vietnamese culture has a lot of Chinese influence, so yes, there are strong ties to East Asia. We’ve also served as the oppressor to other SEA ethnic groups. But our history of occupation and colonization, entangles us with our SEA neighbors. The issues that our people, especially as refugees or as family of refugees, face in America and other Western countries overlaps with those of other SEA. It’s easy to generalize and say our people have benefited from the Model Minority narrative as many of us have gained upward mobility here in the States. This privilege that a lot of us have experienced in larger Viet communities around the country (i.e. OC, Houston, San Jose) may have relegated us to being a prime “wedge group” within American racial politics. I’ve seen people playing into the “Good Refugee vs. Bad Refugee” fallacy. I cringe thinking about how so many Vietnamese Americans are anti-Syrian refugees. It’s like they’ve forgotten much of America felt the same way about Vietnamese refugees in the 70s and 80s.

I want to elevate the SEA voice within the larger API umbrella, but it’s a challenge as most of the influential API orgs seem to be dominated by East Asian leadership. They’re all lovely people and many are extremely conscious, but I constantly feel like I’m on a hunt to find more SEA people who are as passionate as me about carving a space for ourselves. In LA, especially, a lot of us have stuck to the broader API identity/community, but at the risk of getting talked over. A lot of the conversations I’ve had recently question the reality of why we — East Asians, Southeast Asians, South Asians, Pacific Islanders — are often just lumped into one racial category. There's also Central Asians who are completely invisible. Do we now also include West Asians in the API umbrella? I understand the political power we can harness by being this massive Asian diaspora, but it doesn’t make sense when the experiences, and even physical/ethnic phenotypes, are so unique and different from one another.

There are a few additional discussions I really want to see more of us engaging with. First, we need to address mental health amongst SEA. There needs to be more resources available to those within the SEA umbrella, specifically refugees, that have lived with untreated PTSD. My parents luckily found upward mobility after settling in the states, but my mom struggles with multiple chronic illnesses I suspect manifested from her untreated PTSD.We need to consider how our families’ recent ties to war and colonization correlate to the socio-economic struggles many SEA families face. Yes, there are some Filipino and Viet families earning a household income above the national average, but studies show other ethnic groups in the SEA diaspora falling far below it. Second, I hope the general SEA community, especially the ones thriving, will do the work of showing up for other struggling minority communities. This goes back to my prior statement about wanting Viets to be more political. We need to be taking the risk to support the refugees of other ethnic groups currently seeking asylum. We need to examine the anti-blackness socialized within all of us. We have to stand with the Latinx and indigenous American communities. We must embrace those inside and outside our community who identify as LGBTQIA+. My fairly liberal-minded parents barely bat an eye when I came out to them about my bisexuality, but I do think my parents are the exception. I know plenty of other queer SEAs but it feels like a “hush hush” topic in many households. At the end of the day, I want us all to be questioning how our struggles may have been institutionalized and socialized deeply within our families. The only way I believe we can fight this is to fully engage with our own community issues but to also tear down our programmed prejudices against other minority groups.

My dream for this and future generations is for us to be more intersectional. To truly integrate different minority communities. Everyone needs to educate themselves on what’s outside their immediate bubbles. Many seem only concerned about the issues that affect themselves but don’t bother to learn about what’s happening beyond. Everything, then, becomes divisive. We start playing this game of “Oppression Olympics” and we begin using the ideas and tools of the white patriarchy as weapons against each other. I really dream of a day when we all can be better allies to one another. We’re all hurting in some way, we’re all hurting differently. But it takes a lot more to admit that there will always be someone hurting more than ourselves. In order for us to really progress politically and socially, Viets need to question some of our community’s conservativeness. We need to be willing to have more nuanced conversations about all these difficult to talk about issues. We need to practice empathy.