Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

My name is Vi. My homebase is the Bay Area, and I currently live in Portland where I go to nursing school. I love connecting with people and telling stories through photos and narratives.

What is your family’s immigration story? When and how did they arrive in the United States?

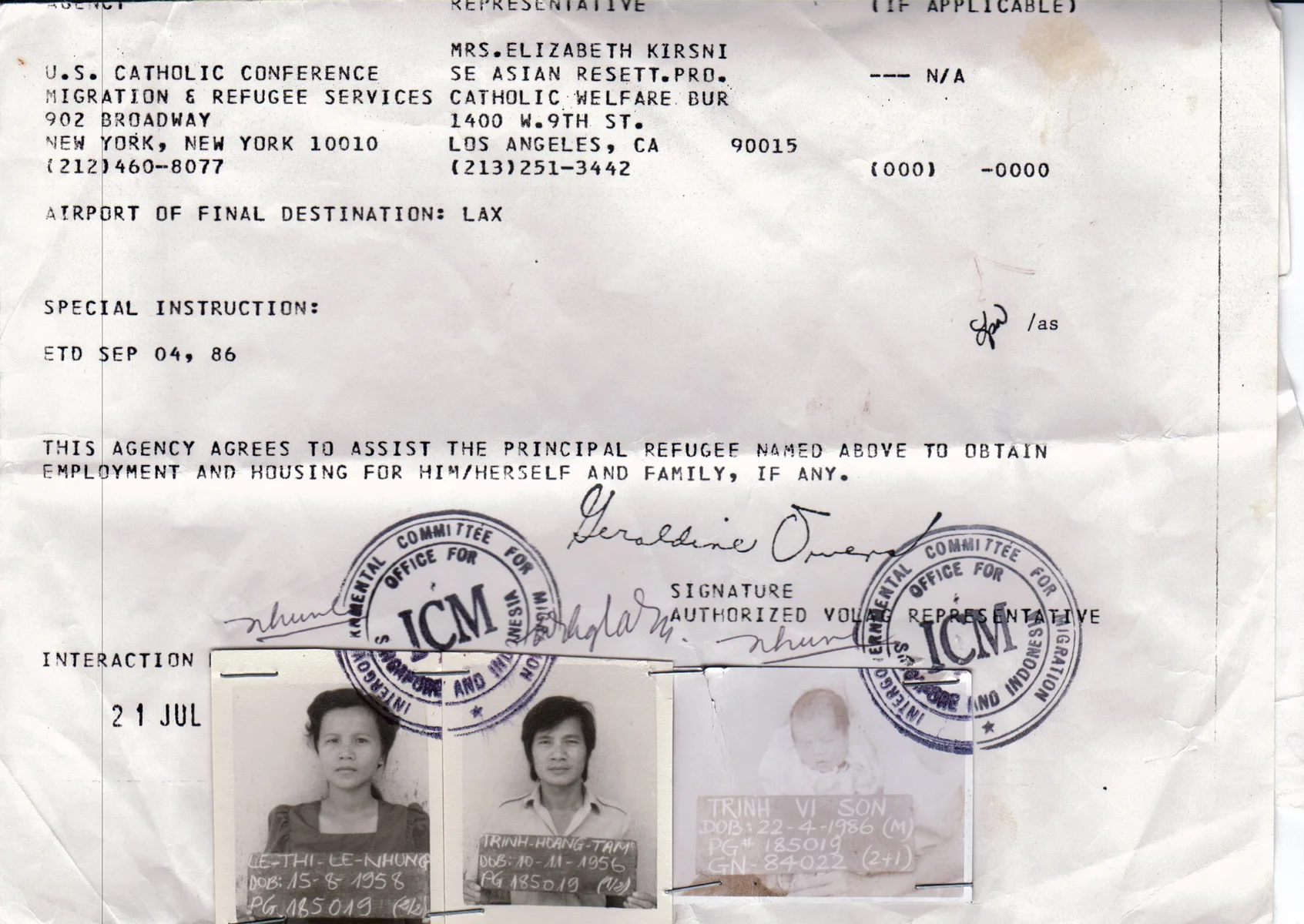

My parents are from South Vietnam: my dad, who is half Chinese and half Vietnamese, is from a small village by the Mekong River called Tra On, and my mom is from Saigon. My parents met in school where they both were learning to be teachers, my mom a chemistry teacher and my dad a general instructor. After the war, my parents tried to flee three times, and were finally successful in 1986. My sister was one year old at the time and because my family felt that she was too young for the journey, she stayed behind in Tra On with my paternal grandparents. On the day they fled, they paid for passage using jewelry, and escaped on a fishing boat with 30 or 40 other people on a journey that lasted 7 days and 7 nights. My mom used to tell us a story about how when she was on the boat, she got so seasick and spent a lot of time just laying on the deck, and one time my dad was looking out at the horizon and saw a whale swimming nearby. She says that if it wasn’t for this whale, their boat would have been capsized by the storm they were trying to weather. I don’t know how true this story is or if it is the result of an hallucination, but the size of the whale was able to affect the strength of the currents and help the boat get to safety. My parents ultimately ended up at Galang Refugee Camp in Indonesia.

I was born in Galang in 1986 and my mom remembers how on that day, there was a holiday or an event and so there was not a lot of medical staff available. My dad had to help with my delivery, and luckily they were able to eventually find a doctor. We were in Galang for about five more months before being sponsored by family to Los Angeles.

My parents work in nail salons, as many Vietnamese do. We lived for about 10 years in LA: East LA, Glendale, and Alhambra. I did not actually meet my sister until I was about 8 years old, and did not even know about her until a few months beforehand. It was a shock to me since I had always thought that I was the oldest child — I have a brother who is four years younger. Then we moved to the suburbs of Chicago because there wasn’t a lot of nail business there compared to the saturated market in LA, and we ended up staying there for 5 years. When it was time for college, I knew I wanted to get away for awhile so I followed my sister, who was studying at U.C. Berkeley at the time, to the Bay Area. I enrolled at Contra Costa College and later transferred to U.C. Davis.

What was it like for you growing up as a Vietnamese American? In what ways do your parents or your culture shape your identity?

Growing up in LA, I did not really think about my identity because I was surrounded by Vietnamese people all the time. When I moved out to Chicago however, all my friends were White, and it was the time I realized what it meant to be the Other. I tried everything I could to slip off anything that was remotely close to my Vietnamese identity: I grew my hair out long and wore a hemp necklace, and I asked my mom to not cook specific dishes and my parents to not sing cai luong or karaoke when my friends came over because I was so embarrassed. It’s cringeworthy to look back at those memories and think about how ashamed I was to be Vietnamese at the time, how anxious I was to assimilate.

When I moved to the Bay Area, the yearning to learn more about my culture kicked in, especially after I found out about Thao and the Get Down. She is unlike any other Vietnamese musician I have ever met, and I love how she finds ways to thread her experience as a Vietnamese American woman into her music. Also, when I went to UC Davis, I was actually very close to minoring in Asian American Studies, and though I was only one class shy, I would have had to stay an extra quarter. The classes I did take taught me so much about different Asian American experiences, and allowed me to really immerse myself in a field that had never been available to me before.

My move to Portland also ushered in a renaissance of what it means to be Vietnamese American. Before when I visited Portland, I thought it was a hipster’s dream with coffee shops, art, bookstores, and creative types — much more of a tourist’s perspective of Portland. It was not until I moved there last year that I really started to think about my own survivorship, how the lack of diversity overall just had a big toll on my psyche. For example, I would feel this sense of fear when I walked alone at night because there were no people of color around in case something happened to me.

Having experienced my parents’ struggles of being immigrants in this country as both an observer and participant, I gained a strong sense of grit — no matter how hard life slaps me in the face, I know you have what it takes to get through it. My parents love to speak in proverbs; no matter how chaotic things are, my mom always manages to slip in proverbs. Her favorite is Có công mài sắt có ngày nên kim, which translates to “If you put in the work to sharpen the steel, it will eventually turn into a needle” or in essence, if you keep putting the time and effort into the skill you are truly passionate about, you’ll be able to achieve your dream. She also always says, Còn nước, còn tát, which means if there's life, there's hope.

Was there ever a moment when you felt extremely ashamed or extremely proud to be Southeast Asian?

My mom is a tenacious woman. She needs to bargain for things, even if they have a fixed price, trying everything she can to get the price down because that’s her way of surviving in this capitalist society. I even remember her trying to bargain the cost of my braces! I remember feeling slightly embarrassed whenever things like that would happen, but I was never extremely ashamed.

My ability to draw inspiration from the stories of my parents and my other family members and to turn them into an art form is something that gives me a lot of pride as a Vietnamese American. My parents set up this anchor and it’s up to me to carry the baton and create my own stories based on our generation’s experiences and help them transcend to the next generation. I have shown some of my work to my parents, and it’s a different type of proud than you would expect — more or a head nod and an, “Okay.” In terms of my art and my creative expression, I’m sure they’re proud deep down (though they will probably never vocalize it), but they might be more visibly proud when I get my nursing degree.

As well as being a nursing student, you are also a documentarian, a person who writes and collects photos or footage or memorabilia to tell stories. Some of your collections speak so deeply to our shared experiences of being Southeast Asian American, including At Sea and Free and My Chinatown. What do these two projects mean to you as a child of refugees and of diaspora?

My parents have been my primary inspiration for my passion in visual storytelling. When I was young, I recall my parents sharing their experience and stories as Boat People in different intimate family moments —dinner, family gathering, evening car rides. So when I started At Sea And Free, I wanted to honor that experience by curating and capturing images that continues that legacy. My Chinatown on the other hand, is a project that not only captures day-to-day moments of Chinatown from different cities, but is also an opportunity for viewers to observe these captured photos from the eyes of an immigrant — like myself. Chinatown was one of the first cities in which my family acclimated when we were newly arrived immigrants in 1987. So much of my memory in Chinatown revolves around walking through the streets —while different shops and people blurred past my eyes. 30 years later, I tried to embody that experience through the way how these photos were captured. So in short, At Sea and Free is a reminder that I am in fact a refugee with a complex lineage, whereas My Chinatown is my refugee experience navigating through a new community that has made my family feel at home.

Description for Vi’s “At Sea and Free” collection, taken from his website.

Description for Vi’s “My Chinatown” collection, taken from his website.

Another project that we are absolutely mesmerized by is The Stories We Carry, created by you and your friend Andy Nguyen, a Vietnamese American Nurse Practitioner based in Oakland and born and raised in Portland. This collection almost seems like the perfect cross between At Sea and Free and My Chinatown, a beautiful representation of past meets present. Can you please tell us the inspiration behind it?

When I was younger, I was going through a photo album that my parents had kept when one photo in particular caught my eye. It was an image of my dad when he was around my age in a refugee camp in Indonesia, standing there with his arms crossed in front of a series of paintings that he had done. I had never seen my dad paint; I had seen his sketching here and there, but his main priority in the States had always been working. I realized that I had never really thought about my parents outside of their roles as Mom and Dad, and that there were parts of them that I didn’t know. This moment and this photo inspired me to start my The Stories We Carry project.

In the process of collecting these family photos, I started thinking about how there must be other people out there who have memorabilia that they identify with a lot, maybe something that tells a story about their lineage or a struggle that they had gone through. The idea of expressing people holding items in their hands is a literal interpretation of the stories we carry. I also have a fascination with hands, probably a result of my parents working in the manicure business, and when I look at my parents’ hands, I can almost see the stories their hands tell.

Another inspiration for The Stories We Carry comes from an earlier idea for a passion project centered on refugee families. There are already a few photo projects that talk about the refugee experience, but not many that focus on the experiences of the second generation. It’s important to acknowledge our heritage and the legacy of the first generation, but we need to keep the momentum going and look to the present and future as well.

I found the other folks featured in The Stories We Carry through family and friends. I started by shooting my friend Sarah, who is half Saudi Arabian and half White, holding a photo of her parents. Her mom had passed away awhile back, and as a public health educator and a dancer, a lot of her dance pieces reflect her own experiences with grief. After talking to Sarah over coffee, I was so moved and inspired by her story and decided to shift my project focus from refugees to the second generation. I then took photos of my sister holding a picture of my grandfather. From there I just started connecting with more and more folks, and so what started with a single photo has now transformed into something that allows me to connect with other people and build community. My friend Andy, who is also a second generation Vietnamese American, and I were also talking about possibly one day doing a podcast around The Stories We Carry where we go back and interview each of the individuals we featured.

Also, interestingly enough, recently I have been using a film camera, a Nikon F2 and a Nikon F3. The Nikon F series was used in the Vietnam War by American soldiers to document their experiences. So for me, my choice to use these particular cameras is my own little way of protesting, resisting. It’s a simple camera to use, and it’s rugged — it can survive apocalyptic conditions, which explains why it was used in the War. There was an American soldier who was taking a picture by lifting it over his head when suddenly we felt this force that knocked him back a bit. He saw that there was actually a bullet hole in his camera, but the bullet didn’t fully penetrate the camera because of the steel exterior; that photo is now in a museum somewhere.

What is the impact you hope your project has and the conversations it will start?

In terms of the impact I hope my project has, sometimes the artist in me just wants to do projects for the aesthetic and not have to think about the weight of it. But back in 2016, I saw the pictures of the Syrian refugees fleeing in boats and those images immediately reminded me of the Vietnamese Boat People experiences. That moment was a catalyst for me because I realized that I needed to create something that went beyond myself. Especially considering the political climate we have right now, I hope that as this project continues to grow, people from different backgrounds will see it and recognize that there are so many things that connect us all together as human beings.

To see more of Vi’s photo collections, please check out his website: http://www.visontrinh.com. You can also follow him on Instagram @visontrinh, where you can also learn more about the stories behind the photos in the The Stories We Carry collection.

Photos are courtesy of Vi Son Trinh and should not be reproduced without his permission.