Can you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

My name is Peter Trinh, born and raised in Denver, Colorado. I am an actor, playwright, and stand-up comedian. I’m also a father of two boys.

Where are your parents from? When and how did they arrive in the United States?

My mother is from Long Xuyên, and my father is from Thốt Nốt. They met in college at Cần Thơ. My parents escaped Vietnam in 1981 by fishing boat when they both were around the age of 26. They were lost at sea for seven days, finally picked up by the USS Shasta, and taken to the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp in Sembawang, Singapore. By March of 1982, my parents were sponsored to Denver by extended family.

When you were growing up, did your parents ever talk about their experiences of being refugees?

My parents’ refugee story was always something I knew since I was young because my father always talked about it. I think it was important to him that both my brother and I knew these things – the understanding that “this is what we went through and this is how it was.” My mother never spoke about it. She recently told me she doesn’t like talking about such difficult times and sadness.

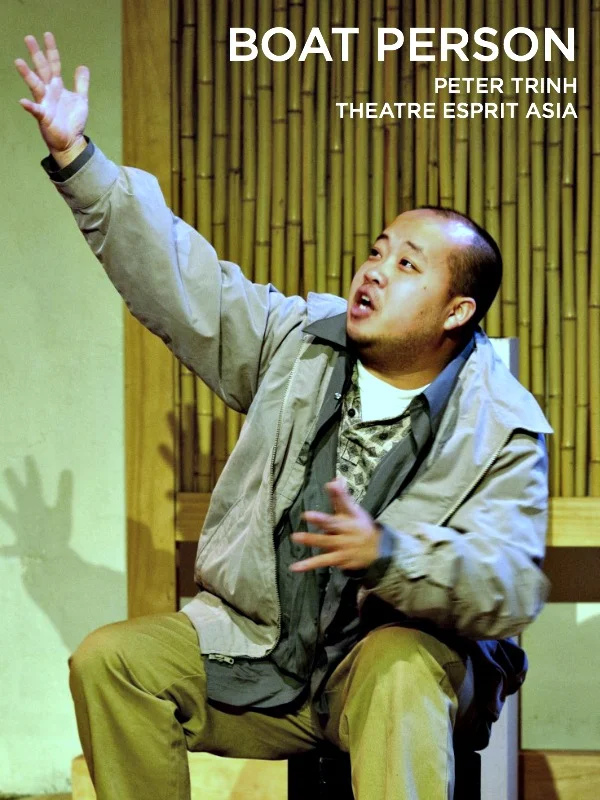

After hearing bits and pieces, I sat down and taped my father reciting the story from start to finish, and in 2015 wrote my play Boat Person, chronicling their escape. My father had told me once about how my parents never had a marriage ceremony. He considered that time, the escape, as their honeymoon. It was exciting and crazy and they were newly married. They were embarking on a new life together at 26 years old.

They had me shortly after arriving in the U.S. In the play, I talk about how a month after I was born, the blizzard of 1982 hit Denver, bringing almost four feet of snow – to this day still the biggest snowfall ever. I remember being 26 – I had my first child at 26 – trying to live life normally and I couldn’t imagine being in a new country seeing snow for the first time going through all that my parents went through.

How would you define the “Model Minority Myth"? Has it played a role in your own life?

To me the model minority, as it pertains today, are minorities who benefit from society while simultaneously remaining unseen or unheard: “We’ll allow you to live amongst us, so long as you contribute and we can easily ignore you.”

I was constantly told growing up, “Đừng có làm phát!” which essentially means “Don’t be a bother/Don’t make waves.” I didn’t listen very well. It seemed no matter where I went or what I did, I drew attention to myself and was consistently challenging authority. Blossoming into adulthood, I learned to embrace my outlook. I am one of only two people in my extended family who is artistically-minded, and perhaps the most liberal. I like that my personality “breaks the mold” and I find people of all backgrounds are more attracted to me because I am not meek and quiet.

Also, I never performed well in school. I was obviously smart and excelled where I applied myself. The problem was that I was easily bored and more interested in the social aspect of school. For example, I was accepted in Gifted & Talented, but failed it. I remember in Junior High, I was called into a conference with my science teacher, Principal, Assistant Principal, and my father. They had “concerns” because I was not performing as well as “other Asian” kids the science teacher had had. My father was embarrassed. I was outraged and blamed the teacher for being discriminative. But the reality was that I was never heard, and nothing happened to correct this discrimination. I was left to believe it was all my imagination. It took me a long time to realize I was indeed treated with prejudice.

When and how did you become interested in acting?

When I was 5 years old, I was at a family event. While entertaining my cousins with impressions of my drunk uncles, my cousin Rose exclaimed laughing through tears, “You should be an actor!” I remember that moment vividly. In an instant everything made sense. I have always loved film and found solace in memorizing and reciting my favorite scenes.

How did you become a part of Theatre Espirit Asia, the Southwest's first and only Asian American theatre company?

Theatre Espirit Asia (TEA) was conceptualized in the dressing rooms of a production of Joy Luck Club at Vintage Theatre in Denver back in 2012. The founders, Maria Cheng and Tria Xiong, approached me to join on the board and read their proposed first production, Dust Storm. I declined a formal position at the time, but instead I was cast in their inaugural production of Dust Storm – a Japanese story about the internment camp. In 2016, TEA offered me a position as Assistant Artistic Director.

At present I have stepped down from TEA, though I still support their endeavors. I have found I am not very suitable for art administration. Being Assistant Artistic Director meant sitting in board meetings, city council meetings and I just didn’t get the same feeling as being on stage, and so I have refocused my career on performing and writing.

Could you speak a little about recent productions you’ve been acting in? What motivates you to choose these projects? And how do you deal with being typecast?

Recent productions include Arabian Nights and Chinglish, where I spoke only Mandarin and had to learn my lines phonetically. I have also recently shot some independent films.

Luckily enough, there are not many male Asian actors in the Denver area, so roles have a way of finding me. But I am mostly attracted to stories that have a creative way of speaking to the human condition. I love to do mostly comedy – even though I’ve been doing a lot of dramas. I like roles that are not any specific type – not specifically Asian but more about the comedy of the character. But I do find I get mostly typecast. For instance, I’ve played a couple dozen doctors. I’ve filmed a couple independent films and in one I played a drug addict, the other I played a drug dealer.

Deciding whether to do a role that’s stereotypical – it’s the kind of thing as an Asian actor you have to weigh; it’s a job. You don’t really choose what you go out for a lot of the time. Because it might perpetuate stereotypes, you have to think to yourself, “Do I want to do this?” But you have to get paid.

I find the one way to deal with it is to make your character as realistic, believable, authentic as possible. If you make characters who are believable as people even though they are in these stereotypical/typecast situations, that’s what the audience is going to identify with. The stereotype can be overlooked if the character is authentic.

The industry is rampant right now with whitewashing roles and Asian stories centralized around White saviors. But I also think this subject is coming to a head. This is the perfect time for Asian artists to get their voices heard and to put our stories out there.

Speaking of Chinglish, it is a play that is almost completely in Mandarin. How did you prepare for the role, especially since you don’t speak Mandarin?

Chinglish almost didn’t happen because it was so specific: it needed people who could speak Mandarin and were of Chinese descent. Michael Chen and I are probably the only Asian male actors in the city. And it became this thing where you want to help the community – someone picks up a play and they want to do this play so they call you.

So they finally found a new Chinese actress who was a film actress from China. But as a recent immigrant, she’d never acted in America and she hadn’t done any stage acting. It almost didn’t happen but we took her on. In addition, they got a high school girl who was Chinese but adopted – she and I had to learn Mandarin phonetically. We had a coach and everything since 60 percent of the show is in Mandarin. And on top of that, just weeks before the show, I had to learn seven more pages of Mandarin.

Chinglish was a big hurdle, but I like to put myself in situations where I have to rise to the occasion. If the opportunity comes, I’m going to take it. And if down the road I’m faced with a similar challenge, I now know it’s something I can handle.

What inspired you to write Boat Person? What were the reactions to it? What strengths or weaknesses does a one-man play give to this refugee story?

A colleague of mine approached me and asked if I had a story to tell for a collection of one-act plays. Having always wanted to put my parent’s story to paper, I dove in. The project was lower budget, so the play naturally lent itself to be a one-person show. Also, I had done two other solo works prior, so I felt confident in producing my own.

I’ve performed Boat Person in Colorado cities like Denver, Fort Collins, and Lafayette. I’ve also performed it in Minneapolis and New Orleans. People have stopped me in the bathroom after the show and they’re just speechless. They say they didn’t know that that happened to the Vietnamese people. And because it’s an immigration story, it speaks to all immigrants of different backgrounds.

The challenge of a one-man play is not having the dialogue and interaction. The character has to be very defined to properly convey your story. However, the upside of a one-man play is the narrative. As the actor paints the story, we follow along the journey because the performer connects directly to the audience and TELLS the story more than just shows.

Anything in the works that you’re allowed to give us a sneak peek of? What’s next?

I’m on a pretty big hiatus – I’ve done a couple projects here and there, including a few indie films. On this hiatus, I’m going through a life transition focusing on my kids, who are 4 and 8. I’m probably going to take another year off.

As for what’s next in my career, I’d like to be a working actor going forward. I do have my Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and Actors Equity Association (AEA) invites. A lot of people in Denver shy away from going professional because you’re not allowed to do non-union shows, and that may diminish the number of shows they do a year. But doing union shows ensures I get paid well, and since I’m a parent I only do a couple shows a year. Traditionally, these jobs would be more abundant on one of the coasts, but Denver’s changing. There are rumors of a kind of Hollywood-style lot being built near the airport. I’m pretty rooted here with the kids, so I’ll probably not be leaving the area anytime soon.